When Payne returned to the States, he traveled the country with John James Audubon, becoming a champion of Cherokee Indian issues.Įventually, through political connections, Payne was appointed to an unlikely position: He became consular general to Tunis in 1842. He acted with Edgar Allan Poe’s mother and unsuccessfully tried to court Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. He would write more than 60 theatrical works, mostly adaptations, while becoming friends with prominent visiting or expatriate Americans such as Washington Irving and Benjamin West. He “suffered financial difficulties his entire life,” says Hugh King, director of a museum dedicated to Payne in East Hampton, New York.ĭespite financial setbacks, Payne’s career flourished in Europe. Payne was the least benefited of all concerned.”Ĭopyright laws were practically nonexistent in those days, and Payne saw little money from “Home, Sweet Home!” in either Europe or America. “Still,” writes Harrison, “with all the success of the opera and the publication of the song, Mr. When the nobleman reneges on his promise of marriage, Clari, surrounded by the trappings of palatial life, longs for the humble but wholesome home she was duped into leaving.Īccording to Gabriel Harrison, Payne’s 19th-century biographer, the song “at once became so popular that it was heard everywhere.” More than 100,000 copies were printed in less than a year, netting huge profits for the publisher. The show’s climatic number was “Home, Sweet Home!” sung by the title character, a poor maiden who has become embroiled in a relationship with a nobleman. Clari, or the Maid of Milan, debuted in London in 1823. Once released he worked with Covent Garden Theatre manager and actor Charles Kemble to transform a play into an operetta by altering the plot and adding songs and duets. An unsuccessful attempt at managing a theater house landed him in debtor’s prison for a year. Payne was also writing, adapting and producing plays. The handsome young man went on to play the starring role in Romeo and Juliet and is believed to be the first American actor to play Hamlet. “Nature has endowed him every quality for a great actor,” wrote one reviewer.

He earned rave reviews for his performances at the famous Drury Lane Theatre. In 1813, he arrived in London, sent there through the largesse of friends eager to help further his promising theatrical career.

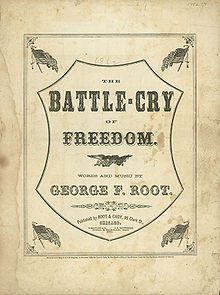

There are several accounts of Confederate and Union troops camped near one another harmonizing "Home, Sweet Home!" across the battle lines. Published anonymously (who would take a 14-year-old seriously as a drama critic?), The Thespian Mirror made a big impact in the theater community and set Payne on the road to a career as a writer and performer. Instead, he was sent to work as a clerk in an accounting firm, where he managed to find time to create a newspaper devoted to the theater. The son of a schoolmaster, he showed great promise performing in school productions but was dissuaded from the theater-hardly a respectable profession in those days-by his father. Born in New York in 1791, Payne was a precocious talent, an intimate to some of the greatest creative minds of his age, a wanderer and a fellow with a knack for bad money management. Sadly it did little for the man who wrote it. When Patti offered to sing another tune, Lincoln requested “Home, Sweet Home!” It was, he told her, the only song that could bring them solace. When Italian Opera star Adelina Patti performed at the White House in 1862, she noticed Mary Todd Lincoln-still mourning the death of their 12-year-old son, Willie, from typhoid fever-crying during the performance and the President holding his hands over his face. Eventually the Union authorities prohibited the regimental bands from playing the song fearing it might make the soldiers too homesick to fight.Ībraham Lincoln himself was a great admirer of the song. There are several accounts of Confederate and Union troops camped near one another, perhaps just across a river, the night before or after combat, harmonizing “Home, Sweet Home!” across the battle lines. Indeed, Payne’s plaintive refrain “there’s no place like home” does not arouse martial instincts. “It gets me every time,” admits Jolin, who plays banjo, harmonica and dulcimer. The song is “Home, Sweet Home!” by John Howard Payne. Rather, it is a piece written in 1822 by a talented American who was already nine years in his grave by the time the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter. When folk musician Tom Jolin performs Civil War songs in concert, it’s not “When Johnny Comes Marching Home,” “The Battle Cry of Freedom” or any of the other standards of that time that really tugs his heartstrings.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)